Betrayal, bribery, and ambition plagued European politics in the 17th

century. Alliance came and go and war remained constant to grab as much

territory as much as possible for whatever the reason. The War of Devolution (1667

-1668) illustrated this.

Causes of the War of Devolution

King Louis XIV of France, the Sun King, took absolute power over France

after becoming his own chief minister with the death of the last Cardinal Jules

de Mazarin. A young, active, and energetic ruler, Louis wanted to prove his

fitness as King by establishing himself as a great military conqueror. France

just welcomed peace after concluding a stalemate war with Spain in 1659 with

the Treaty of Pyrenees. Though the Treaty deprived him of a marriage based on

affinity, it did gave him a basis in launching a war.

|

| King Louis XIV |

The Treaty of Pyrenees cemented peace with the arrangement of the

marriage of Louis XIV to the Spanish Infanta or Princess Marie-Therese. This

formed a bond between 2 rival houses of Europe, the House of Bourbon and the

House of Habsburg. However, not even marriage had the capability to cement

ties, maintain peace, or keep the ambitions of a powerful monarch such as

Louis. Louis used the Pyrenees Treaty and his marriage as a key to acquire new

lands for France.

King Philip IV of Spain, father of Queen Marie-Therese, passed away in

1665. The Spanish throne fell to the Queen’s feeble and physically deformed

younger brother from his father’s second marriage, Charles II. Louis exploited

the weakness of the new Spanish monarch to his advantage along with a knowledge

of the laws of inheritance of the Spanish Netherlands.

|

| Philip IV of Spain |

Spanish Netherlands practiced devolution. Unlike most of Europe

favoring the first born son in inheritance, the region’s devolution prioritized

children from the first marriage regardless of gender. However, Louis needed to

cover a loophole in his justification – Queen Marie-Therese already renounced

his claims to the Spanish Netherlands. Determined to keep the war a rightful

and legal cause, Louis argued that in 1659 the Queen renounced his claims to

the Spanish Netherlands for a huge dowry worth 500,000 ecus to be paid by Spain

to France. Spain never paid the dowry, hence Marie-Therese stake to the lands

remained. Louis XIV used this as his justification for a war.

|

| Brussels, Capital of the Spanish Netherlands (c. 1610) |

Geopolitics played also a factor in Louis decision to go to war.

International politics in 17th century mixed kingdom rivalry with family

rivalry, such the case of France and Louis XIV’s House of Bourbon. The Bourbon

and French had an archrival in form of the Hapsburgs of the Holy Roman Empire,

a rivalry that dragged on for centuries prior and later on. The Hapsburgs

placed their scion around France with a Hapsburg King in Spain, Spanish

Netherlands, and finally the Holy Roman Empire. This made Louis anxious over

threats of invasion in multiple sides. He then set out to secure the Kingdom by

establishing buffer zones between Hapsburg territories and France. This became

his objective throughout his reign. In 1662, he already secured Dunkirk, a

major port city in the English Channel. He also wanted to secure open areas for

an invasion in Alsace-Lorraine, Franche-Comte, and finally the Low Countries.

Conflict

Timing of French invasion went perfectly for Louis. The French King decided

to launch his invasion at a time when most of Europe’s great powers had their

own conflicts. Spain fought an independence war in Portugal. English and the

Dutch fought with each other. Only the Holy Roman Empire remained a possible

challenger of the invasion.

|

| John IV of Portugal proclaimed as King |

Invasion began on May 24, 1667. French Marshal Viscomte de Turenne, a

veteran of the Thirty’s War and the French Civil War called the Fronde, led

70,000 troops and overran the Spanish Netherlands. Few cities resisted with the

longest and greatest being the city of Lille. Here the talents of military

engineers such as Chevalier le Clerville and Comte de Vauban contributed in a

French victory over the Spanish Netherland cities.

|

| Vicomte de Turenne |

The Holy Roman Empire and its Emperor Leopold I, however, turned a blind

eye over the invasion. The Empire and France already began negotiations for the

possible partition of the Spanish Empire. By January 1668 the countries agreed

in time of death of the sickly Charles II of Spain, France would recognize

Leopold as the new Spanish King in exchange for vast territories including the

Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, the Philippines, and Navarre. As a result,

the Holy Roman Empire showed indifference over the invasion.

Dutch reaction, however, came as a surprise to the French. Louis

expected Dutch support just as the French showed the latter against the English

in the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664-1667). During the said war, Louis naval

forces prepared to support the Dutch in their strike against the Royal Navy

anchored in the Thames and Chatham. Then suddenly, the Dutch betrayed him by

condemning the invasion. Worst, he faced a threat of a war against a triple

alliance.

The Triple Alliance of England, the Netherlands, and Sweden formed as a

result of the invasion. England and the Netherlands saw the French advance as

threat to their security. England feared for their access to the continent

while the Netherlands feared for their independence. Therefore, with a common

enemy in sight, on July 31, 1667 the 2 countries concluded the Second

Anglo-Dutch War with the Peace of Breda. The 2 countries then enlisted the

support of the superpower of the Baltic Sea Sweden, who reluctantly joined in

exchange for subsidies it badly needed. In January 1668, the Triple Alliance

demanded the French to cease their advance. The Alliance then threatened if

France compelled otherwise, they would mobilize their militaries with the aim

pushing the French out of the Spanish Netherlands erasing all their

advancements for the past months. Besides the Triple Alliance, events in the

Iberian Peninsula pressured Louis further.

Spain gained a free hand in February 1668 when its war with newly free

Portugal. In exchange for Spain’s involvement, England and the Dutch prepared

to pay subsidies. With pressure mounting, France secured further gain before

ending the conflict.

Franche-Comte became the new theater of the war. Between March and

April 1668, the Prince de Conde marched with another French army to capture the

region vital to the security of France from Central Europe. Cities in the

region like Artois, Besancon, Dole, and Gray fell immediately cementing French

annexation.

Resolution

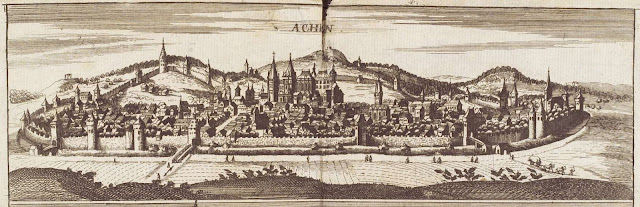

|

| Aix-la-Chapelle (1690) |

The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle put an end to the War of Devolution on May

2, 1668. Under the Treaty, France kept most of its conquest in the Spanish

Netherlands except for the cities of Cambrai, Aire, and Saint-Omer. In

exchange, however, she returned to Spain the newly conquered region of

Franche-Comte. Hence, French objective of securing buffer lands remained

incomplete with only few lands being taken at the war’s end.

The aftermath of the war left few years of peace for Europe. The War of

Devolution signaled French claims over the Spanish Netherlands for the rest of

the reign of Louis XIV. Ultimately, another Franco-Dutch War erupted in 1672, 4

years after the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle.

Summing Up

The War of Devolution came only as a small conflict, but with profound

message. It set the tone for the foreign policy and military goals of the newly

energetic King of France Louis XIV. It signaled Europe to watch out for King

Louis XIV determined to cement France as the superpower of the world.

The conflict also displayed the international political mood of the

century showing the role of personal ambition mixed with that of the kingdoms

of rulers. It showed the importance of balance of power in Europe that made

alliance and animosity between countries fragile. Countries’ fought each other

for their own interest, but expressed willingness to cooperate once a common

enemy appeared. Indeed, there is no permanent enemies, only permanent interest.

In summary, with a chaotic political atmosphere and an aggressive

powerful and ambitious ruler determined to prove himself as a conqueror, the

War of Devolution was only a tip of the iceberg of conflicts that plagued

Europe afterwards that made and broke Kingdoms.

See also:

Bibliography:

Websites:

“Devolution, War of (1667-1668).” Encyclopedia.com. Accessed on May 11, 2019. URL: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/modern-europe/wars-and-battles/war-devolution

Mongredien, Georges. “Louis II de Bourbon. 4th prince de Conde.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Accessed

May 11, 2019. URL: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-II-de-Bourbon-4e-prince-de-Conde

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “War of Devolution.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed May

11, 2019. URL: https://www.britannica.com/event/War-of-Devolution

Book:

Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis

XIV, 1667-1714. New York, New York: Routledge, 1999.

.JPG)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.