Legendary Beginning

The Aztecs or the Mexicans as they called themselves descended from 1 of the 7 tribes living in the mythical Aztlan. From there they began an epic generations-spanning journey to find their new homeland. Across time and space, the Mexicans found guidance from their war-god Huitzilopochtli.

The story of the migration began in Aztlan or land of heron and from which the word Aztec originated. Huitzilopochtli, the blood addict war god, guided the Mexica people to leave Aztlan in search of a “promised land”. And so, the Aztecs marched south, establishing towns and villages, being embroiled in a divine family drama, and fighting hostile tribes. They embarked in a journey filled with numerous episodes of Deus Ex Machina.

| Aztlan in the Aubin Codex |

The journey took about a century, with the Aztecs staying in some spots for a decade or two. One episode, Huitzilopochtli ordered the Mexica, in the dead of night, to go march on, abandoning his sister Malinalxochitl and her followers due to her brutality even for his standards. The abandonment led to resentment by Malinalxochitl who passed this outrage to her son Copil.

Copil, thirsty for vengeance, caught up with the Mexicans who by then settled in the hill called Chapultepec. The angry Copil convinced the surrounding tribes to besiege the Mexicans who then guided by Huitzilopochtli snicked into the furious nephew, slew him and took out his heart. They then threw the heart into some spot in Lake Texcoco.

Nevertheless, the Mexicans abandoned Chapultepec and found refuge among the Culhuacans. Despite the considerations offered to them and driven by Huitzilophochtli, the Mexicans flayed a Culhuacan princess as an offering leading to them being chased out. Huitzilopochtli then told the Mexicans to return to the place where they threw the heart of Copil which by then grew into a barrel cactus that attracted to perch on top of it an eagle clutching a snake. After immeasurable patience, resilience, and obedience, around 1325, the Aztecs found the spot and there established their capital: Tenochtitlan.

Reign of Acamapichtli

Unlike the land of milk and honey promised to the Israelite, the Mexicans settled for a swamp surrounded by more powerful tribes. If the Mexicans did not perish through hunger and exposure, war threatened their existence. In this perilous time of early Tenochtitlan, Acamapichtli took the mantle of leadership.

|

| Acampichtli |

The Mexicans, toughened by journey, resolved to survive in the swamp given to them by Huitzilopochtli. Life, nevertheless, remained difficult with food and water scarce and threat of conflict, in particular with the powerful Tepanecs of the city-state of Azcapotzalco and their leader Tezozomoc. The clan leaders of the Mexicans then decided to elect a tlatoani or speaker, representative, and leader with connections and sophistication.

The council settled with Acamapichtli, a half Mexican and half Culhuacan related to the royal family of the latter tribe. Acamapichtli then went into Tenochtitlan to fulfill his duties and solve the prevailing problems of hunger and threat of war.

Acamapichtli took a path of building the strength of the Aztec and bidding time taking a pragmatic diplomacy with the Tepanecs. He accepted to be a tributary of Tezozomoc, paying high amounts of tributes. A high amount Acamapichtli accepted to preserve peace.

The high tribute, however, strained further the food needs of Tenochtitlan. In another divine intervention episode, Huitzilopochtli comforted his people by promising bountiful harvests to meet their own needs and the tribute payments. Acamapichtli then ordered the wide use of chinampas, a special Mesoamerican cultivation technique in lakes, to produce food.

|

| Chinampas, 1912 |

For about 2 decades, Acamapichtli’s decisions that secured food and peace succeeded in establishing a reputation which the Mexican widely recognized. As Acamapichtli passed away around 1380s or 1390s, the Mexicans clan leaders decided to elect his son, Huitzilihuitl to the position of tlatoani. Hence, Acamapichtli’s line supplied Tenochtitlan with leaders up to the time of Spanish conquest.

Reign of Huitzilihuitl

Huitzilihuitl built up from the foundations his father laid. He continued to be pragmatic and strategic, using marriage to his advantage. His reign raised living standards and set the stage for the Aztecs to take the center stage.

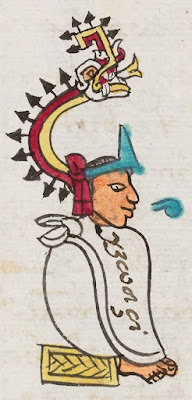

|

| Huitzilihuitl |

By the time of Huitzihuitl’s election, Azcapotzalco and its ruler Tezozomoc remained the dominant power in the region around Lake Texcoco. Huitzilihuitl then proposed a marriage with one of Tezozomoc’s daughters. The Azcapotzalco leader agreed to give his daughter Ayauhcihuatl. Huitzilihuitl then proposed another marriage, this time to the Tlacopans, tying the knot with Miyahuaxochtzin. Finally, he also married the princess of Cuernavaca (Quauhnahuac) Miyahuazxihuitl, despite opposition from the bride’s father and ruler of the said state.

The marriage brought many benefits to the Mexicans. Towards Azcapotzalco, the marriage brought relief in terms of the amount of tribute payment and share in conquest and military experience from Tezozomoc’s wars. With Tlacopans, they gained a significant ally in the region. Finally, with Cuernavaca, the Mexicans gained access to cotton allowing them to improve their clothing leaving behind maguey fibers.

In other words, Huitzilihuitl’s pragmatic and low-key diplomacy allowed the Mexicans to become a player in the politics of the region. His marriages improved standard of living and gave Tenochtitlan clout. Eventually it finally set the stage for a showdown and the rise of Aztec power.

Reign of Chimalpopoca

Chimalpopoca reigned short, but his rule turned out to be a crossroads in Aztec history. Being the grandson of Tezozomoc, it placed the Aztecs in a position to finally challenge the might of Azcapotzalco. His demise led to the Aztecs’ rise.

|

| Chimalpopoca in the Tovar Codex |

The Tepanec civil war ended with one of Tezozomoc’s sons, Maxtla, becoming the leader of Azcapotzalco. Maxtla wanted to secure his position by eliminating all claimants to the throne which pointed towards extended family members including Chimalpopoca. By the order of Maxtla, Chimalpopoca fell to an assassin.

Chimalpopoca’s uncle, Itzcoatl took the position of Tlatoani and with the help of the new Tlatoani’s nephew and brother of Chimalpopoca named Tlacaelel, they used all the might build up from the time of Acamapichtli into good use. With their alliance with neighboring cities, they formed a Triple Alliance that avenged the death of Chimalpopoca. In the face of a combined might, Azcapotzalco fell.

|

| Itzcoatl |

Rise of the Aztecs

Patience and resilience formed the backbone of the Aztecs character from the time of their migration to the early times of Tenochtitlan. Blessed with pragmatic and strategic leaders, from Acamapichtli to Huitzihuitl, the tragedy of Chimalpopoca became an opportunity. Itzcoatl and Tlacaelel used all what their relatives prepared for to finally topple the old elite and established a new order. From the Triple Alliance that defeated the old power, it formed the foundation of what later became the Aztec Empire. The Empire that dazzled and later fought the Spanish conquistadors in 1521.

See also:

10 Things to Know About the Early Leaders of the Aztecs

Bibliography:

Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, Domingo de San Anton Muñon. Translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Susan Schroeder. Codex Chimalpahin (v. 1). Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Duran, Diego. Aztecs: The History of the Indies of New Spain. New York, New York: Orion Press, 1964.

Fehrenbach, T.R. Fire and Blood: A History of Mexico, A Bold and Definitive Modern Chronicle of Mexico. New York, New York: Collier Books, 1973.

.JPG)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.