From

632 to 661, in a spanned of just 30 years, an empire emerged on the back of a rising

religion – Islam. This spectacular expansion of territory and religion came

under the leadership of the deputies of Islam’s founder Mohammed – the Rashidun

Caliphs.

Early Existence

The

Prophet Mohammed passed away in 632 and left a Muslim community in Mecca and

Medina bent on spreading the religion either through by peace or war. He left

no instruction as to who would succeed him as the leader of the new community.

The Companions of the Prophet thought of this issue deeply when they met in

Medina. They immediately disregarded passing the leadership to the children of

the Prophet due to their gender – 4 daughters. Alas, they had to choose between

acknowledging as their leader the male relatives of the Prophet or through

election. This contention later sow the seeds of the demise of the Rashidun

Caliphate.

|

| Abu Bakar |

Eventually,

they chose an election and this Abu Bakar al-Siddiq (r. 632 – 634), one of the

earliest apostle of the Prophet, emerge as their new leader. He along with his

4 successors came to be known as Rashidun Caliphs or the Rightly Guided. They

took the title Kalifa or Caliph meaning deputy with the task of leading the

Islamic community forward. Abu Bakar had the respect of many because he was

among the earliest converts of Islam. He also earned confidence the same way as

the Prophet showed him chosing him while the latter was ill.

Abu

Bakar met an immediate daunting task. Although the Muslim community stood

strong and growing after the death of Mohammed, some Arab tribes, however,

chose to leave Islam and revert back to their old religions. They also refused

to pay taxes to Medina viewing the Prophet’s death as the end of their pledge

of allegiance and obligation towards the polity he left. Abu Bakar must then

reassert Islam’s rule over these tribes through war that became known as

al-Ridda War.

The

new Caliph Abu Bakar proved himself a great leader. He won the al-Ridda War and

the Peninsula became totally controlled by Islam. The reach of the religion

also expanded beyond the Arabian dessert and in time gained new converts in

neighboring countries such as Yemen.

Internally,

Abu Bakar organized the government of his caliphate and a standing army bent in

spreading Islam through a Jihad or Holy War against infidels or non-Muslims.

Abu Bakar, however, failed to see the expansion. He passed away in 634, ruling

only for 2 years but he secured a strong foundation for the Rashidun Caliphate

to build from.

Expansion

After

Caliph Abu Bakar’s demise, the Companions of Mohammed met once again for an

election. This time, Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634 – 644), went to be the winner

and the 2nd Rashidun Caliph. His rule saw military expansion against their

powerful neighboring empires of Byzantine and Sassanid.

Umar

came from a humble background and not as prominent as other Companions. He appeared

as a humble and honest leader and a strong military commander proven by

entering a war against the empires of the Christian Byzantines and Zoroastrian

Sassanids. His choice to attack the 2 empires came timely as both had been

tired from decades of fighting each other. Thus, the growing incursions of the

Muslims in the borders immediately became a cause for concern for the empires.

In

634, the great General Khalid ibn al-Walid led his army to victory against the

Sassanids in the Battle of the Chains. Such the battle’s name due to the

Persians army soldiers wearing a chain in their feet to prevent their

desertion. After this major victory, another followed, this time against the

Byzantines. The magnitude of Muslim attacks grew from raids to a major

invasion. In 636, a Muslim army under Generals Khalid ibn al-Walid and Abu

Ubaidah bin Jarrah fought an army way larger than theirs in the lengthy Battle

of Yarmuk. The battle ended with a complete Muslim victory and the whole of the

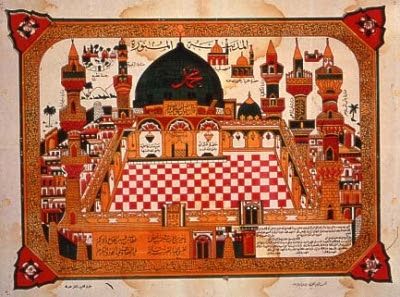

Levant, including the Holy City of Jerusalem, and Egypt came under the fold of

the Rashidun Caliphate. The 3 Holy Cities in Islam – Mecca, Medina, and

Jerusalem – was finally under the control of the Rashiduns.

More

victories followed Yarmouk. In 637, the Battle of Qadisiya against the Sassanid brought Iraq and parts of Persia under the Muslims. A year later the Sassanid capital

of, Ctesiphon, fell to Muslim commander Saad al-Waqqas. In 641, ancient cities

of Mosul and Babylon fell to the Arabs after the Battle of Nahavand. The

Sassanid King fled and avoided capture for years to come.

|

| Taq-i Kisra in Ctesiphon |

A

key to the success of the Muslim expansion seemed to be their religious tolerance.

Unlike the Persian Sassanids and Byzantines, Muslims allowed other religions to

continue their worships as long as they pay an extra tax called Jizya. They welcomed the Muslims as

liberators from the oppression and persecution of the Sassanids and Byzantines.

With

a growing Empire at his hands, Umar moved to consolidate his rule through the

creation of a new administrative structure for the Rashidun Caliphate based on

Sassanid and Byzantine organization. He created an executive council composed

of representatives from Muslim and non-Muslim communities to advise him in

matters of state affairs. By emulating the Sassanid and Byzantine local

administrative apparatus, he hoped to use the local expertise of the newly

conquered people to govern and maintain peace in the far flung regions of the

Caliphate.

Umar

created provinces and appointed governors tasked of collecting tax and maintain

peace. He imposed strict punishment on tax evaders. And in order to keep

satisfaction within different localities, he allowed taxes to be spent locally

first before sending the surplus to Medina.

Furthermore,

inspired by both Empires again, he borrowed the idea of land taxes and imposed

the kharaj. Aimed towards non-Muslim

property owners, it boosted further the Caliphate’s revenue. It also led to the

creation of a land registry and record the taxes due to a particular area.

Non-Muslims manned this registry due to the lack of Arabs capable of manning

this foreign task.

With

growing revenue from taxes on Muslims, the Jizya, and the Kharaj, the Caliphate

soon had more money than they could count. It resulted to the creation of the

public treasury office called Diwan,

an Arabic word for ledger. The early Diwan received the task of managing the

finances of the Caliphate as well as monitor the salaries of the army. The huge

wealth also resulted to the world’s first government pension where the

Caliphate paid its citizens based on their time length as a Muslims,

contributions to the expansion of Islam, and their social status.

Under

Umar, Islam continued to shape itself. He introduces the Islamic Calendar with

the starting year from the Hegira. Work on the Quran also began.

In

644, Umar fell to an assassin’s blade, in particular, of a Christian slave. The

assassination put Umar in his death bed where he designated a council to elect

his successor. He soon passed away leaving an Empire that covered the Arabian

Peninsula, Persia, the Levant, and Egypt – a new force to be reckoned with.

|

| Uthman ibn Affan |

The

council appointed by Umar deliberated and choose between Uthman ibn Affan and

Ali ibn Abu-Talib, a relative of the Prophet. In the end, Uthman (r. 644 – 656)

emerged as the new Caliph and under him expansion furthered with modern day

Armenia and Libya falling to the imperial Caliphate. In 651, the last Sassanid

Emperor was captured marking the final demise of the Persian Empire.

In

religious affairs, under his rule, the compilation of the Quran was

successfully completed. It contained the teachings of the Prophet and arranged

from the longest to the shortest.

Although

the Rashidun Caliphate continued to grow, internally, Uthman was unpopular. His

clan, the Umayya opposed the Prophet during the early years of Islam and even

supported his persecution. Also, many criticized the Caliph for his nepotism

and favoritism towards his clansmen. His unpopularity burst into violence in

656 when a mob attacked his home in Medina and killed him.

Decline and End

After

the fall of Uthman, a new election brought to power Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656 –

661). Many Muslims saw his election as long overdue and viewed him actually as

the first deputy of the Prophet. His rule, however, became marred with civil

war – the first Fitna. Ali urged by

Muawiya Abu Sufyan, a relative of Uthman and then head of the Umayya Clan, to

punish the murderers of Uthman. Ali, however, knew the murderers supported him

and delayed and even tried to avoid punishing them.

This

action of Ali led Muawiya to refuse to pledge his allegiance, making him in open

rebellion. A divide then emerged openly within the Islamic community. One side,

the supporters of Ali called Shia’t Ali or supporters of Ali, simply Shia,

fought the traditionalist or those who supported the election of Caliphs called

Sunni or men of the tradition. The divide in the first Civil War of Fitna led

to a split that continued to rage to this day.

In

the end, the Sunni and Muawiya won the civil war when Ali was assassinated in

661. Muawiya established the Umayyad Caliphate that continued the expansion of

the empire and its consolidation under an organized government.

See also:

Bibliography:

Hunt, Courtney. The History of Iraq. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Koehler, Benedikt. Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism. London: Lexington Books, 2014.

.JPG)

.jpg)

very misguiding article

ReplyDeleteb

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete